On today’s episode of the Financial Independence Podcast, I finally got to interview the person who introduced me to the concept of financial independence and early retirement in the first place…

Jacob Lund Fisker from Early Retirement Extreme!

To my mind, Jacob is the founder of the modern-day “FIRE movement” so hope you enjoy the interview!

Listen Now

- Listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

- Download MP3 by right-clicking here

Highlights

- What Jacob has been up to since stepping away from ERE

- His experience being a financial quant and how it impacted his personal investing

- The problem with set-it-and-forget-it index investing

- The importance of staying flexible with your investing strategy

- Predictions for the next decade and the post-COVID world

- A systems approach to lifestyle design and why it’s beneficial

- Jacob’s thoughts on early retirement how they’ve changed since publishing Early Retirement Extreme

- His current projects and his plans for the future

Show Links

- Early Retirement Extreme Website | Book | Forum | Wiki | Audio Book

- Early Retirement Extreme on Twitter | Facebook

- ERE 10-Year Update on Get Rich Slowly

- The Post that Started the Mad Fientist’s FI Journey

Full Transcript

Mad Fientist: Hey, what’s up everybody?

Welcome to the Financial Independence Podcast, the podcast where I get inside the brains of some of the best and brightest in personal finance to find out how they achieved financial independence.

I can’t believe it, but I am finally interviewing the person that introduced me to this whole idea of financial independence in the first place.

And that is Jacob Lund Fisker from EarlyRetirementExtreme.com.

I came across Jacob way back in 2011, I was reading GetRichSlowly.org, which I’ve interviewed the writer behind that blog, JD Roth, on a previous episode of the podcast. So I was reading his site, and he did a review of a book called Early Retirement Extreme, and it just blew my mind. And that was when I realized that early financial independence was possible. If you saved enough money, you could then live on it and not have to rely on work anymore. So I’d say that was probably the most influential article I’ve ever read in my life, because it completely changed everything. And over the years, I’ve heard lots of stories from people about who introduced them to the idea of FIRE. And, you know, Mr. Money Mustache is a big one. And even this podcast has introduced some people to the concept, which is amazing to me. But Jacob and ERE is what did it for me. So it’s an honor to be able to talk to the guy that changed my life in so many ways. So rather than ramble on here, I just want to dive into it…

Jacob, thank you so much for being here. I really appreciate it.

This is a long time coming. So I started this podcast way back in May of 2012. And you were going to be my first guest, because you were the entire reason I knew about this whole thing called financial independence in the first place. But I chickened out and ended up asking a guy named Mr. Money Mustache, who was also a software developer like myself. And thankfully, I didn’t know how big he was at the time and how big he would go on to become but yeah, this is, this is a huge treat to be able to talk to you after all these years. And to thank you for the huge impact you’ve had on my life. Because I was trying to think about it before this call and I can’t think of anyone other than maybe my parents and my wife who have had a bigger impact on my financial life than you have. And it was all from an article on Get Rich Slowly. And I think it was maybe when JD was reviewing your book back in 2011.

Jacob Lund Fisker: Yeah, I mean, I think that was the one. I recently did a 10 year update and Get Rich Slowly as well. But I think that like only only two of them. But like, at that time I was I was I was mostly sort of like fading out of existence, like right when you started is when I more or less ended.

Mad Fientist: Yeah, it was crazy. You just passed the torch to Mr. Money Mustache and that’s why I was like, well, I could talk to him because he’s a software developer. That would be fun. And yeah, it was just around that time.

Maybe that’s where we can kick off because I’m interested to hear what you’ve been up to. So you had you had written the book. And it’s a fantastic book. I’ve read it at least three times. And you finished up what you were trying to say with the website. And you were moving on and you passed the torch to MMM and I believe at the time you were becoming a quant trader. Is that right?

Jacob: Yeah, something I never quite sure what my title was actually supposed to be. But it was me staring at financial data…a giant screen setup and trying to see some patterns there.

Mad Fientist: What was that experience like? And how long did you end up doing it for?

Jacob: I was there three and a half years until 2015. Essentially, my experience…when I was sort of like a young physicist, so to speak, I was very dismissing of anything financing business. But as I sort of like, matured a little bit more and got into sort of like the postdoc era of my life, I began to sort of kind of get acquainted with the whole financial independence thing, I started reading into finance and economics and actually thought working in the business and Wall Street could be could be really fun. And but that was that unfortunately happened sort of like around 2007-2008.

And then the great credit crisis essentially happened then there was like, tons of layoffs and all hiring essentially froze. And then I thought, Well, okay, that’s kind of like it for me. Just kind of forget about that.

And so I basically did that. And when I was sort of writing on the blog, instead and I was always making these kind of comments about like, if there had been more physicists on Wall Street, maybe this wouldn’t have happened. Like total physicist arrogance, we can fix everything.

And then one of one of my readers actually commented back and said if I’m still interested, maybe he could make that happen. So I was like, Yes. Okay, let’s try this, right, because my sort of philosophy is to try as many different things as you possibly can so essentially, sort of like self actualize to the fullest. By doing many different things, I’m learning many different things. So he essentially got me into the company in Chicago. So we left California in 2011-12. So basically, just before you started podcasting.

So same time, I sort of took that as an opportunity to stop blogging because I really felt that I but said everything there was to say, in the blog, I finished the book, which was sort of like the canonical textbook of both FI and also sort of like the extended theory part of it, I mean, to be FIREd, it’s just like a small aspect of what, when I was sort of like going on about so so I did that for a few years.

Yeah, I think the greatest takeaway…is how big a difference there was between, like the academic side, sort of like the internet armchair expert, and then the actual practitioners. Because in other fields, like science and engineering, you’re used to having one line of insight, sort of like goes from not knowing anything to maybe being like a hobbyist to being like a serious amateur. And then you have people working in the business. And then at the very top, you have like professors who understand everything. That, you would agree, is typically how it goes. I don’t know if that goes away in computing these days. But that’s how it would go in and like for example, physics, whereas in, in finance, or high finance, or like Wall Street stuff (Wall Street does not mean the physical location essentially means everything that has to do with trading and making deals that are outside the retail level), it has essentially forked. So they’re like two different communities that almost have like a wall between them. So you have, you have the academic side of it. And then you have the practical side. And what’s weird is that like the practical side is way bigger, way more well-financed, and in a sense more advanced. Whereas the academic side, they have essentially access to worse data, because data is expensive. So it will be something like end of day closing prices, you can get a subscription to that. On the actual practitioner side, you will have everything tick by tick from multiple different exchanges. There’s not just the market in the US. I mean, when I when I quit in 15, there were like 40 different I think, exchanges and dark pools just in the US. So way more data, and that sort of like leads to sort of like different interpretation, different behaviors in those separate groups.

And yeah, so that was my biggest surprise. My biggest insight from it was probably how agnostic or how neutral people were, in practitioners are in terms of like, what’s the best strategy is more sort of like, Well, I mean, this strategy might be good for this. And this might be good for that. But all sort of like look at what works and and just go with that. It’s not like as a theoretical academic level, where it’s all an improvement and stuff we already know and Nobel Prize winners have shown that and therefore everything must cite back to something, some previous work.

I sort of like the more dogmatic so I mean, I think that sort of like spilled over into the rest of my life. So these days, I’m so far less to sort of like fly off a tangent because someone is wrong on the internet. So I think that is sort of like the biggest life lesson in that.

Mad Fientist: That’s a great takeaway. Did it affect how you view your own personal investments at all? I know back in the day, when I was reading you, you were one of the people that wasn’t on board with the whole buy and hold index investing, just set it and forget it sort of thing, which I want to dive into a little bit more. But first, did did your time in the industry on that practitioner side of Wall Street? Did that influence how you invested as an individual or a family?

Jacob: Not really. I mean, first of all, it’s like what I was was doing was like completely different than what I can do as a retail investor. So no, that’s not really been any change, I will actually say I’m probably better as a retail investor than I was as a professional. I tend to be more risk adverse, and this is not optimal for the industry. Let’s put it that way.

Like one of the fun things, where every everybody I work absolutely enjoyed playing poker. And I hate poker. I mean, that was interesting. I think in terms of the whole sort of like the index investing thing. I think the my reputation has been somewhat exaggerated in the FIRE movement. I mean, I wrote a few posts and asked some questions about the systemic effects mass adoption of index investing could have on the markets as such. And that sort of eventually turned into, “this Jacob guy who just hates index investing”. I think my bigger concern was the whole fire-and-forget attitude. Let’s, just hand everything over to an app. Let’s, you know, you want to want something quick and easy, something simple. So just do that. And then you can forget about it.

Mad Fientist: I’d be interested to hear what you think of the FIRE movement? Especially, I think maybe 2017-2018 just seemed like it was going crazy. What were your thoughts on it at that stage? Because this is, you know, seven years after you felt like, you’ve pretty much said everything you wanted to say about it?

Jacob: Yeah, I mean, it’s kind of like doing the podcast today. It’s like, well, man, I just like the 10 years ago, I’d forgotten all about it right now. And I need to revisit my notes, essentially. Yeah, I mean, it definitely hit the mainstream at that at that point. And, you start getting contacted by various journalists, because I mean, I’m sort of still known as one of the progenitors of it. And so of course, they want my opinion on it.

And I think what happened, essentially, you get, like a different kind of different kind of exposure. I mean, if you started if you go like, way back, way back, if you go back to sort of like this, the present iteration, which I think kind of started with me, we were only like, at least I was sort of like the loudest loud mouth bunch, right? I mean, I remember sort of, I mean, back then FIRE was not a thing, that sort of financial independence was not a thing in the personal finance world. I mean, when I was starting up, I was like, you know, these like, blogging awards, and I was I was getting them for, for something like “Best in Senior Living”.

Like “Best Entrepreneurial Blog”, like I hadn’t started into business, but that was sort of like the sort of the framework of sort of like the mid late 2000s that financial independence could fit into.

And so I started out at this very extreme kind of thing, way out of the left field, you know, like, let’s try not buying anything for a year. So that was completely unusual to do that. And when this has now become sort of like a “Buy Nothing Year”.

Back then was David Bach thing where it was like the latte effect, where if you just save $2 a day, you become a millionaire in like 100 years, or whatever, and the idea of retiring was that you would save up a million dollars, it was always a million dollars, so that he was to become a millionaire. Investing, I think, like the 4% rule…that was the thing. But it wasn’t really that wide widespread. I mean, it came out of the Trinity study but back then the Trinity study was only like 10 years old or something. So it was not the foundation of any way to sort of invest for retirement. It was more like I want to retire on this day and I have the $700,000 and I want to spend $40,000 a year, and then they would go back way around and then compute like a return of investment of 6% and so given those 6% what should the allocation investment be like. So that was sort of like pre 4% rule as a as a rule of thumb and a lot of people retired and invested accordingly.

Right. And that kind of goes back to that warning about not adapting or sort of like integrating a very simple understanding of how to invest for the next 60 years, because some of these guys, you know, like, who retired in the 90s. And it was sort of like a mental model that sort of crashed and burned, because investing in some something aggressive at 8%, which was perfectly possible in the 90s, did not work very well between 2000 and 2007.

Mad Fientist: So, would you be willing to share like sort of what your thinking is, as far as personal investment now, and like, you don’t have to obviously share any numbers or any actual strategies, but maybe just give a sort of an idea of what you’re thinking as far as how you invest your own FI portfolio?

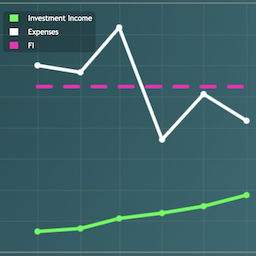

Jacob: Having invested for almost 20 years, now, I can definitely say that it changes, I mean, it changes, you change, depending on where I make money, I don’t make money. Depends on how big the network has become. I mean, if you are like starting in the beginning, then index funds, for example, makes like great sense. Because you’re not you don’t have to think very much think very hard about and you can concentrate on your salary instead, I mean, and sort of like a we agree way to identify that demographic is when they plot you know, your net-worth graphic, and it’s just a straight line up, right? Because stuff, you know, your dollar cost averaging is completely and utterly dominating the sort of market impact of whatever your net worth is like, maybe you’re, you probably have sort of like less than 10 to 15 annual spend so that’s essentially how we calculate net worth these days, like how many years of spending have saved. So if you’re below 15, then you know that the net worth curve always tend to be a straight line, because it’s dominated by salary. But then once you sort of get into get into the 25 Plus, and if you get even higher, I mean, my problem is, essentially, I spend so little that whenever people pay me money, I don’t know what to use it for. So this like, just keeps going, going up and up and up. I mean, right now, it’s like 130. And from that perspective, you know, like, volatility, or risk…risk for me is no longer volatility risk, for me is a permanent loss. Right? Maybe that’s another sort of like practitioner takeaway. These guys don’t care about volatility, they care about money that never comes back, right? Because volatility is only really relevant if you’re like, if you’re doing research, then volatility is sort of like, sort of like a very easy way to define risk, because you can calculate, you know, it’s the standard deviation, essentially. And it’s useful if you’re, if you’re a bank, and you’re sitting in the middle between a customer and a big pool of money, because I’m here to sort of like bridge between and you have like slippage losses. But for practical people, that’s the risk of permanent loss. So my personal strategy has tended towards becoming like a lot safer, you know, like belt and suspenders kind of stuff.

My interest in investing, investing is also kind of going down. So I actually might end up just like, putting everything into a Global Fund, or something

I think I worry most about are the cases where someone comes in and says, I don’t care anything about investing or finance or anything, I just want sort of like a one stop solution for my post-FIRE life. I don’t know what what to call that risk…like an ignorant risk or paradigm risk?

Because I mean, paradigms change. I mean, they change every 10 years. I mean, you only have to go back 10 years, look at the real estate bubble, and see how that was sort of like, in many ways in the US, not in Canada, where it didn’t pop. But here, it was many ways driven by by sort of the same dogmatic slogan based understanding that you tend to see in sort of, like, I wouldn’t say it’s like the entire FIRE movement, but there are many, many in the, in the fire movement that have had sort of like the same thing like, well, they’re not making any more land, just by the biggest house, you can, because you’ll never get this chance again. They’re not making any more often. Just paint the walls essentially.

And you can, you can go back and see these kinds of ideas like fail over and over and over again. Because people change their mind. I think it’s like a twofold I mean, you can sort of feel the two ways you can have the paradigm shift under you, and then essentially like miss the terrain. Or worse, you can keep insisting that that one strategy you learned when you’re 25 is still valid when you’re 50, right?

So like, so the dominant paradigms are essentially been index investing since the 2010s is like when that exploded, and part of the reason it exploded was, of course, because interest rates were both dropped and then you had all these quantitative easing things, both in the US and in Europe. And you could actually plot like the stock market index with bands when when you have quantitative easing, the market goes up, when the easing stops, it goes flat. When it started again, it goes up again, you know, that’s not that’s, that’s not really a booming economy. That’s like, an economy, on heroin or something. I mean, that’s just bad. And then you can’t keep doing that forever. What I mean, so far, so good, right?

And if you if you sort of, if you said like this is what’s actually happening in, in sort of, like the practical world, and on Wall Street, I mean, I knew a bunch of like, value investors. That’s not what I was doing, but people doing value investing, and sort of like getting depressed. Because everything was like completely overvalued. There was like nothing to buy that made some sense, right? So they’re just sitting on piles of cash waiting and waiting and waiting. And if you’ve been waiting for 10 years, right?

You can’t keep insisting that you are right and the market is wrong. I mean, you can only do that so long. So that’s the tricky part.

Going back, so you had like real estate in the 2000s. And a little bit again after it recovered, people got into it again, and now it’s called house hacking. It’s always a new new word.

You had .coms in the 90s but obviously, not anymore, right?

A little bit again…the five biggest companies in the s&p 500, that’s 20% of the index, right? They call the giants like Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Google, and I totally forgot one. And they’re like, 40% of the NASDAQ. How’s that for diversification?

Anyway, go back again…So in the 80s, it was commodities and CDs, like bank CDs, because the interest rates were so high. You can’t get anything out of that anymore. So like a safe CD investment from the 80s would completely bomb, right.

70s, gold. My uncle collected stamps. Essentially because the market flatlined, and bonds were not doing anything so people were just buying collectibles, thinking that that would sort of be the thing.

In the 60s, it was like blue chips. I just want to buy the big companies, and you’ll be safe forever. And as a result of that the multiple expansion was immense. So similar to what you see today, in internet stocks, you know, we had like PE ratios above 50. So like, that would take decades for these people to actually like return a decent amount of sort of like economic profit, as opposed to just like greater-fool profit of people like buying higher and so on.

So I mean, the thing is, the biggest mistake one can make is to believe that you, you know everything there is to know about investing. But sort of like you have this kind of like dogmatic mind. I’m not kind of like super insist that everybody become an expert on this. But I do think that I think the least people can do or should do is sort of like pay attention from time to time, like is index investing still a thing? And if it is, cool…just keep doing that. But if everybody around you have sort of like moved on to something else, whatever that is, maybe it’s time to start questioning whether you are still the genius you think you are right.

Mad Fientist: I think that’s great advice. And it seems like right now is potentially a paradigm shifting event COVID and then all the money being pumped into the economy. What are your thoughts on that? Have you have you spent any time thinking about what this means for the next decade? And what’s going to be the big thing for that? Because it does seem like this is a turning point, potentially, in how people think of investments and what the government’s ability to get involved is.

Jacob: Oh, well, investment wise, I haven’t really done much. I was already like a belt and suspenders.

I mean, it was kind of shocking to see things dip that fast, right? That was crazy fast compared to say 2008. 2008 was sort of more like a slow grind. I lost 1% today, tomorrow I lost another percent. And after 30 days, you know, you’re just sort of getting punished every every day until you’re sick of it. And then when when the maximum number of people were sufficiently sick, it flipped, because there were no more that were willing to sell and it went up again.

Here, it was more like slam slam, and then suddenly way up again…it was crazy volatile.

So there was like a lot of people in the futures market that just had like a field day with that. So for them it was good but for buy-and-holders, it must have been very interesting.

But of course, the government immediately practically guaranteed all their corporate bonds, right. So they were dropping. So you have like AA rated bonds, that should normally be almost like treasuries losing, I don’t know, 20-30% like over a week. I mean, that’s insane. And then they gain it just as fast, as the government comes in and backstops the whole thing. What’s more interesting to report on COVID from the ERE perspective, because ERE was originally not intended to be some FIRE thing. It was certainly more intended to be be sort of like a resilient lifestyle, like a low resource intensive lifestyle. So if we were to run into limits to growth in the environment, would it still be possible to live live well. And so for me, it has always been about, highly efficient living, and how to make it resilient and not become financially independent, as much as becoming like economically dependent, like independent of the economy. And so that, essentially is like ERE at the higher level. And if you do that, then FIRE just become a nice side effect. You know, if you have a job, people pay you money, but you don’t have anything to use it for so you just park it in a savings account, which is actually what I did myself for, like the first five years until I found that there was something called investing and the crazy idea, like using money to make more money. I mean, that was just bizarre to me. I mean, I’m an immigrant. I’m from Denmark, where like, stock investing was not a thing, and really wasn’t. Put money in bricks in housing, but owning stocks and bonds, that was just weird. So with COVID, you know, being independent of the economy already, there was like practically no change in the way we live here. And on the forum, we had sort of like a slight tension between what you would call like the traditional FIRE people sort of like high incomes and total belief and like comparative advantage…it’s kind of like the, I’m not gonna spend my time fixing a flat on my bicycle for $15 when I’m making like $50 an hour. So you see that attitude a lot, especially the more people earned, the less they are willing to deal with the little things.

And they suddenly realize, it doesn’t really matter I have all this money when everything is on lockdown and I can’t do anything. Whereas for sort of like the resilient system I build up and then some of the other guys that build up instead it was like wow, this is what we’ve been prepared for practically. And so there was actually a lot of shifts in sort of like the one dimensional money only consumer/producer kind of thing, towards the sort of like more systems theoretical way of integrating your production and your consumption in your personal life so you’re no longer just having money coming from this side, so you earn it here and then you buy stuff here to solve the problem. It was more like the total solution.

Mad Fientist: That’s one of my favorite parts of the actual book. And ERE is one of my favorite finance books and it’s not even really a finance book, as you said. It’s more a philosophy book about overall life strategy and systems and yeah, the the financial independence part is a byproduct of that life but it’s the systems approach to lifestyle lifestyle design that I really enjoyed and I still think about it a lot.

Like when Mr. Money Mustache bought that piece of property on Main Street and had this like community thing. I thought, that’s a such an amazing idea because I’m an introverted guy but I do enjoy meeting people in my community and socializing. I was like, that’s a great idea. And now he has this place that just sort of, like promotes that.

And at the time somebody was talking about maybe starting a brewery. And I thought, oh, that would be ideal because you get the forced socialization, you’re building something, you’re building a business, which is always fun and challenging. But on the health side of things, which in your book, you talk about how the second order effects of some decisions and how it could be negative positive. And for something like a brewery, it’d be great for the community, the socialization, the challenge, the creation/creativity, things like that. But it’d be terrible for the health side of things, because I would find myself drinking more beer.

So it’s definitely something that I’ve kept in mind over the years. And it really does help me make decisions. And it’s like, okay, this seems good at first but what’s the knock-on effect? So yeah, I was wondering if you could maybe talk about how you’ve used that thinking in designing your life and how that has made you really resilient for a pandemic?

Jacob: Yeah, I mean, so like, I almost feel like sort of like, describing the whole thing. Like, the book is very much about like, contrasting and comparing what we grew up with taking for granted, which is essentially the idea that you specialize in a job, you get an education, you specialize in a job that gives you earning power, and then you potentially measure how successful you are in terms of how high your earning power is. I mean, in the English language, we even have like expression, how much are you worth? I mean, when, when we ask that question, we want to know, like, you know, it’s the money question, practically.

It’s not like how nice a person are you or what did you do for your community. I mean, it’s really, are you making lots of money. And along the same dimension, happiness equals spending. And I mean, I don’t know if I’m, like, projecting too much, but you can see how, how FIRE kind of developed into lean FIRE and fat FIRE. I’m obviously somewhat even more extreme than lean FIRE, but fat FIRE often sort of accuses us on the other side of like living a life without happiness because we are sacrificing so much, because spending is happiness. So I mean, it’s not surprising, from even like, from you’re like 10 years old, from the time you’re old enough to watch ads, right? I wonder when that when that happens by age three? You do get sort of like continually reinforced that if you buy something, that increases your happiness, you get a shot of dopamine. Or if you had a problem, you pay someone, so all you need to do is earn and then you buy. So you’re in this kind of cycle.

Personal Finance when when I started with it sort of tried to step out a little bit of that. I mean, if you’re sort of into the spending equals happiness, it’s no surprise that like half of Americans end up not having any more than $400 for one emergency. Right? Which is tragic, crazy. I mean, it shouldn’t be that way, right?

So like, initial personal finance then becomes about like prioritizing your spending and not just like blowing your money left and right and then trying to keep everything together with credit cards.

And people started learning how to budget you know, that’s a basic skill. I don’t know if they teach this in schools today. They didn’t when I was young. To a large degree, people are not taught sort of like the fundamentals of the society they live in it’s kind of like fish swimming in water, right? I mean, they’ve not discussed the water ever. So to them the water does not exist. And to a similar degree, the whole idea of earning and buying as a lifestyle is not something people see from the outside. It’s something that they can’t see because they’re inside of it.

So, in the blogging world, it’s almost like getting an education, when you get into this, from sort of being blind to the water and then getting out.

So you learn to budget and prioritize. And then if you’re a little bit more advanced, you start optimizing your budgets. Where is my money spent best or how do I get the best deal out of this. But it’s still sort looked at in isolation. Like, what is the best car here? Does this car make me happy? You know, are we getting the maximum return of my money in terms of like, my choice of driving, how do I make the best food.

So it’s all sort of like seen as individual things to optimize. You want to spend money well so you have all these like Consumer Reports review. And the underpinning of all this is of course, specialization and comparative advantage, people are distinctly sort of like pushed back towards, you just got to earn more money, because you’re wasting your time if you try to learn other things.

You can suspect that half of the economy is just in the, in the business of like creating problems for the other half of the economy to solve.

I mean, this kind of like with the brewery. So you drink beer to become happy, but then you also become unhealthy. And then you have to take some other drug that makes you healthy again, but that drug has side effects. And now you have to take a drug to remove those side effects and perhaps pay someone to administrate that whole business.

So this is kind of where the ERE book, where that philosophy comes in, because first of all, it kind of describes this screwed up system we’re living in. So it kind of like takes the fish out of the water. Look fish, you’re swimming in this pool of water.

So I introduced the concept of the Renaissance man or Renaissance person, which was sort of like an early idea of the Enlightenment. Today, it’s more like a general polymath, I think would be the right word.

But essentially, the idea that humans have potential to become many different things, and you should strive to develop in that way. You can kind of contrast it with today where any kind of education development practically stops after college. But you should also development in many other directions, like you should be healthy, should to be able to sing, dance, play an instrument, create art, all kinds of things.

So essentially, in the Renaissance idea was the view that a person should be skilled in many things, which is like completely different than the industrial idea that you should be like skilled, very skilled but in only one thing.

So once you’re skilled in many things, then that essentially implies that now you can start doing many things, you can do different things, instead of paying someone else to do for you.

That’s kind of what you described with MMM’s mainstreet operation or the brewery.

Everything you do has some outcomes, and it always has more than one outcome. There’s always a side effect, some where you got to sort of ask yourself, is that a productive thing or a bad thing. I refer to those as goals. So like, for instance, like if you had a brewery and you make beer, drink beer, then that has the goal of like making you drunk or whatever. But it also has the goal of making you unhealthy. So goal does not imply anything positive…it is simply an outcome.

And so the systems theory comes in when you start connecting these goals. So instead of just optimizing single points, like which is the best electric car, you begin to consider which side effects does this have. Are there side effects to the side effects? And do I do something that’s productive, but also counterproductive.

And so everything is then arranged and it’s almost kind of like…so a system is essentially like a network. That’s probably the best way to describe that. So in a network you have like nodes and connections. You have computers and cables between them. So it’s like a network and systems thinking essentially means looking beyond the given node or the given action to see what impact does this have on the system itself?

And so systems it’s not no longer the money flowing around like it would be on sort of like the one dimensional linear earn-spend thing. It’s also like happiness, health, meaning, skills. So I call it the web of goals, essentially, but could also call it the net of goals but the reason I call it a web is that if you look at it almost like if a fisherman’s net or web for catching something. Actually a spider’s web is probably a better example. If it breaks in some part, like you fail to reach a goal, like seeing back when I was trying to become like a quant in 2007. And I was reading all these like high finance, like complicated finance, how to price options and all that kind of stuff. But I failed at doing that. So that goal was essentially eliminated. But because it was aligned up with other productive goals, it meant that I could still use that knowledge to invest for myself and not like, you know, do harm to my own financial well being.

So in that sense, the web of goals is extremely resilient. You can cut parts out of it, and it still works.

Whereas if you’re sort of like a specialist, who consumes…if you lose your ability to consume, then suddenly you have nothing, right? That was like the COVID experience, right? Oh, my God, suddenly, I have to learn how to cook my own food, because I can no longer go out seven days a week. That happened to a lot of people, right? I mean, there are people who eat out every single day, they literally cannot fry an egg. I’m not exaggerating.

And the other completely different perspective in the book is, of course, going back to the idea where spending equals happiness…to me spending money is bad in that sense because that implies a poorly designed system. For me, spending money is resolving friction in the system. It’s because something is not moving naturally. It’s not well thought out. So I mean, I’m not impressed when people say, “Well, I spend $100,000 a year.” It’s like, wow, you must have a lot of problems with your system!

And that’s essentially the book in a nutshell. And then there’s like, maybe 20 pages on the math in case you want to declare financial independence. And that’s mainly because I got a lot of pushback, “You can’t become financially independent in five years if you don’t have a million dollars.”

Mad Fientist: So to go back to the system, the web of goals, and the systems you have in place…your systems must have been so dialed in, even back in 2011, just because of the amount that you guys were able to spend per year means that you had removed all the inefficiencies and were able to really just not spend that much. Because I think back in the day, I think it was when you were in San Francisco, which is thought of as a very expensive city. And yet you guys were only spending something like $7,000 a year.

Have you felt like your system has improved even since then? And I’m sure it’s a constant thing that you’re working on and adjusting. And has your spending increased at all over the years or it has it actually decreased since 2011?

Jacob: It has changed. Compared to like a normal consumer, our budget looks completely different. And, like we spent like 60% of our money on unavoidable stuff like real estate or health insurance. We cannot we cannot eliminate it.

So if we move like west of the Mississippi, where real estate taxes are a lot lower, we will be spending even less than $7,000 per person. So like two adults $14,000.

The problem also when you go back for 25 years, inflation becomes a factor. If I spent like $6,000 in 2000, I would not be spending $6,000 today. I’m getting old enough where this seems to become a factor.

But on an absolute level, yeah, about $7,000. We were not in San Francisco, we were on on the other side of the bay. We were on the East Bay.

But we had to rent a house there, until we got the RV, and that exceeded $7,000. But otherwise, since I moved away from home, it’s always been about that low. So I’d essentially kept my student stipend budget ever since then, which is, which is a lot easier than if you got used to living at $50,000 a year, $100,000 a year, then going the other way is a lot harder than not going up in the first place.

What has changed is the system. So the web of goals changed as well. I mean, we’ve tried many different ways to live on $7,000 at this point.

Mad Fientist: So what does life look like since you stopped working as a quant? What have been some of the things that you’ve been interested in learning? Like you mentioned, the Renaissance man idea where you’re constantly learning new things and developing new skills…What’s been keeping you busy since the quant days finished?

Jacob: Yeah, so we bought a light fixer upper. So I mean, that’s another thing where sort of like growing up with a wide assortment of skills. Can they take down a wall and put it up again? And in my case, I came in with absolutely nothing. I mean, I can just about like, drill a hole in the wall. That’s my childhood education. So there was a lot of figuring this stuff out. I renovated our bathroom, I built new cabinets. So I’ve been into furniture making for quite a while. So we fixed up the entire bathroom for 50 bucks, I think. So it’s a learning all these little things. And then recently, I’ve started like building clocks out of plywood.

Mad Fientist: Rereading the book recently, to prepare for this interview…I read it way back when it got released and then I read it again, when I was gonna ask you to be on the podcast five years ago, and then I wimped out and didn’t ask you. So then I read it again, in anticipation for this. And you predict a lot of things and they seem to have been coming true in lots of different ways. So my two questions…is there anything that’s changed that you wish you had written in the book? Has your thinking changed in any ways that you think, “I actually should have changed that”? And also, where do you think these ideas go in the future?

Jacob: Yeah, so it kind of goes back to that thing about working in finance, becoming sort of more neutral in attitude or seeing more perspectives..Definitely when I wrote it, I had one perspective, which was my perspective. And if I wrote it today, it would be less edgy, it would be more understanding of other perspectives. So it’s not just like, these guys are crazy. I think there was there’s definitely been some growing up in that sense. Also, from interacting with different people, I’ve become lot more cognizant of different perspectives and limits and more understanding in terms of…I mean, back then I was like, “Well, here’s the book, you just read it, and then you change your life”.

Now I realize it’s a long process. And it’s not from here to here…it’s more like sort of like a step.

And sometimes people might be sitting on the same level for a long time and be fine with it and then suddenly have some kind of epiphany. But that is not necessarily an epiphany that goes all the way to sort of like what I consider the full ERE. It might just be a next step. So we’ve sort of like mapped out the pedagogical challenges of this stuff.

In terms of the technical stuff, I’m sometimes amazed at how smart that book was. I don’t know if I can write it again like that. Since you go back and you read some things like oh, this is really good.

So it’s kind of sounds a little stupid because I think I should be able to write a better book now but I really doubt myself that I can do that.

I think being more understanding of different perspective kind of tends to clutter the mind. Instead of just presenting one perspective, there’s a lot more, “But what if?” and “What about this case?” and “What about that case?” sort of like taking up my mind space these days.

I wouldn’t say I have particularly more I experience and sort of like the pure technical sense but I have talked to a lot more people since then. So I have their perspective. And of course, one of the huge problems back then was that there will not be many examples to draw on. So it all fell on me, right? I kind of realized that I’m a somewhat unusual or weird person compared to…if you pick some someone at random, right? I mean, for example, we don’t have children. So a lot of people will say, “Well, I mean, that’s easy for him, because he doesn’t have children”. But that’s not the best way to learn…to just try to copy someone and try to be like them. I mean, it’s better to understand why they’re doing what they’re doing, rather than who they are, what they’re doing, and then try to do the exact same thing.

Mad Fientist: Exactly. And that’s why that’s why the book is so good. And I think maybe why it’s so timeless, and why it was just as enjoyable reading over the past few months as it was, you know, way back in the in the day, in 2011, because it’s more like…I think even mentioned in the book, it’s not a to-do list or a guide, or even a map, it’s more a philosophy that you can use to make better decisions, to make your own map and figure out your own to-do lists based on that.

Jacob: I was I was very deliberate, trying to make it as timeless as possible. Or as non-timely as possible. This is also why there’s no sort of deep investment – deep is a very terrible word, it is actually quite deep in terms of investment insights – But there’s no details. So there’s no 10 step to it, just buy this fund and that fund and that fund, and then then you’re good to go.

One of one of my quirky hobbies is to go into a thrift store and then like pick out popular investment books from like the 90s. And the 80s. And the 70s, if I can find them.

Something like from the 80s… how to get rich with CDs. And I didn’t want to have written a book like that. Give someone some advice, and then turns out to be terrible like 10-20 years later.

Mad Fientist: Well, we’re coming up to over an hour already, which is crazy. So I don’t want to take up too much of your time, but if people want to get in touch for any reason, is the forum, still probably the best way to post questions and get answers?

Jacob: Yeah, the forum is where the action is. I mean, it’s, at least some people have figured out the blog has been on like, auto rotation for like, eight, nine years now. I don’t really write anything, but it’s still presenting new stuff.

But I mean, the forum is kind of like the grad school of financial independence, if you want to put it that way. It’s not really a place where you go and ask, How do I how do I set up a brokerage account or something like that?

Mad Fientist: Well, this has been fantastic, Jacob. Like I said at the beginning, you’ve you’ve impacted my life in more ways than I would have even imagined it would have impacted me when I read that article way back in the day. So, thanks for taking the time to do this. Thanks for writing. And writing the book.

I usually ask all my guests this final question…what’s one piece of advice you’d give to somebody who wants to achieve financial independence? And it could be about anything. So I’d be interested to hear what you say.

Jacob: I’m the worst person to ask that question. I would say just find someone who motivates you. You can only learn from someone who’s slightly ahead of you and not someone who’s far ahead of you. But once you’re no longer learning anything from a given teacher, then it’s time to move on to the next teacher. I think the best advice is to find the right teacher.

Mad Fientist: And it’s a good time for that. That’s one big benefit of this explosion in people writing and talking about FIRE…you can find that next step.

Well, thank you so much, Jacob. This has been an absolute honor to speak to you after all these years. So thanks again for coming on the show. And yeah, hopefully meet up with you in real life one day and we can chat about more stuff

Jacob: Once the pandemic is over.

Mad Fientist: Absolutely. Thanks again, I’ll talk to you soon. Take care.

Welcome to the Financial Independence Podcast, the podcast where I get inside the brains of some of the best and brightest in personal finance to find out how they achieved financial independence.

I can’t believe it, but I am finally interviewing the person that introduced me to this whole idea of financial independence in the first place.

And that is Jacob Lund Fisker from EarlyRetirementExtreme.com.

I came across Jacob way back in 2011, I was reading GetRichSlowly.org, which I’ve interviewed the writer behind that blog, JD Roth, on a previous episode of the podcast. So I was reading his site, and he did a review of a book called Early Retirement Extreme, and it just blew my mind. And that was when I realized that early financial independence was possible. If you saved enough money, you could then live on it and not have to rely on work anymore. So I’d say that was probably the most influential article I’ve ever read in my life, because it completely changed everything. And over the years, I’ve heard lots of stories from people about who introduced them to the idea of FIRE. And, you know, Mr. Money Mustache is a big one. And even this podcast has introduced some people to the concept, which is amazing to me. But Jacob and ERE is what did it for me. So it’s an honor to be able to talk to the guy that changed my life in so many ways. So rather than ramble on here, I just want to dive into it…

Jacob, thank you so much for being here. I really appreciate it.

This is a long time coming. So I started this podcast way back in May of 2012. And you were going to be my first guest, because you were the entire reason I knew about this whole thing called financial independence in the first place. But I chickened out and ended up asking a guy named Mr. Money Mustache, who was also a software developer like myself. And thankfully, I didn’t know how big he was at the time and how big he would go on to become but yeah, this is, this is a huge treat to be able to talk to you after all these years. And to thank you for the huge impact you’ve had on my life. Because I was trying to think about it before this call and I can’t think of anyone other than maybe my parents and my wife who have had a bigger impact on my financial life than you have. And it was all from an article on Get Rich Slowly. And I think it was maybe when JD was reviewing your book back in 2011.

Jacob Lund Fisker: Yeah, I mean, I think that was the one. I recently did a 10 year update and Get Rich Slowly as well. But I think that like only only two of them. But like, at that time I was I was I was mostly sort of like fading out of existence, like right when you started is when I more or less ended.

Mad Fientist: Yeah, it was crazy. You just passed the torch to Mr. Money Mustache and that’s why I was like, well, I could talk to him because he’s a software developer. That would be fun. And yeah, it was just around that time.

Maybe that’s where we can kick off because I’m interested to hear what you’ve been up to. So you had you had written the book. And it’s a fantastic book. I’ve read it at least three times. And you finished up what you were trying to say with the website. And you were moving on and you passed the torch to MMM and I believe at the time you were becoming a quant trader. Is that right?

Jacob: Yeah, something I never quite sure what my title was actually supposed to be. But it was me staring at financial data…a giant screen setup and trying to see some patterns there.

Mad Fientist: What was that experience like? And how long did you end up doing it for?

Jacob: I was there three and a half years until 2015. Essentially, my experience…when I was sort of like a young physicist, so to speak, I was very dismissing of anything financing business. But as I sort of like, matured a little bit more and got into sort of like the postdoc era of my life, I began to sort of kind of get acquainted with the whole financial independence thing, I started reading into finance and economics and actually thought working in the business and Wall Street could be could be really fun. And but that was that unfortunately happened sort of like around 2007-2008.

And then the great credit crisis essentially happened then there was like, tons of layoffs and all hiring essentially froze. And then I thought, Well, okay, that’s kind of like it for me. Just kind of forget about that.

And so I basically did that. And when I was sort of writing on the blog, instead and I was always making these kind of comments about like, if there had been more physicists on Wall Street, maybe this wouldn’t have happened. Like total physicist arrogance, we can fix everything.

And then one of one of my readers actually commented back and said if I’m still interested, maybe he could make that happen. So I was like, Yes. Okay, let’s try this, right, because my sort of philosophy is to try as many different things as you possibly can so essentially, sort of like self actualize to the fullest. By doing many different things, I’m learning many different things. So he essentially got me into the company in Chicago. So we left California in 2011-12. So basically, just before you started podcasting.

So same time, I sort of took that as an opportunity to stop blogging because I really felt that I but said everything there was to say, in the blog, I finished the book, which was sort of like the canonical textbook of both FI and also sort of like the extended theory part of it, I mean, to be FIREd, it’s just like a small aspect of what, when I was sort of like going on about so so I did that for a few years.

Yeah, I think the greatest takeaway…is how big a difference there was between, like the academic side, sort of like the internet armchair expert, and then the actual practitioners. Because in other fields, like science and engineering, you’re used to having one line of insight, sort of like goes from not knowing anything to maybe being like a hobbyist to being like a serious amateur. And then you have people working in the business. And then at the very top, you have like professors who understand everything. That, you would agree, is typically how it goes. I don’t know if that goes away in computing these days. But that’s how it would go in and like for example, physics, whereas in, in finance, or high finance, or like Wall Street stuff (Wall Street does not mean the physical location essentially means everything that has to do with trading and making deals that are outside the retail level), it has essentially forked. So they’re like two different communities that almost have like a wall between them. So you have, you have the academic side of it. And then you have the practical side. And what’s weird is that like the practical side is way bigger, way more well-financed, and in a sense more advanced. Whereas the academic side, they have essentially access to worse data, because data is expensive. So it will be something like end of day closing prices, you can get a subscription to that. On the actual practitioner side, you will have everything tick by tick from multiple different exchanges. There’s not just the market in the US. I mean, when I when I quit in 15, there were like 40 different I think, exchanges and dark pools just in the US. So way more data, and that sort of like leads to sort of like different interpretation, different behaviors in those separate groups.

And yeah, so that was my biggest surprise. My biggest insight from it was probably how agnostic or how neutral people were, in practitioners are in terms of like, what’s the best strategy is more sort of like, Well, I mean, this strategy might be good for this. And this might be good for that. But all sort of like look at what works and and just go with that. It’s not like as a theoretical academic level, where it’s all an improvement and stuff we already know and Nobel Prize winners have shown that and therefore everything must cite back to something, some previous work.

I sort of like the more dogmatic so I mean, I think that sort of like spilled over into the rest of my life. So these days, I’m so far less to sort of like fly off a tangent because someone is wrong on the internet. So I think that is sort of like the biggest life lesson in that.

Mad Fientist: That’s a great takeaway. Did it affect how you view your own personal investments at all? I know back in the day, when I was reading you, you were one of the people that wasn’t on board with the whole buy and hold index investing, just set it and forget it sort of thing, which I want to dive into a little bit more. But first, did did your time in the industry on that practitioner side of Wall Street? Did that influence how you invested as an individual or a family?

Jacob: Not really. I mean, first of all, it’s like what I was was doing was like completely different than what I can do as a retail investor. So no, that’s not really been any change, I will actually say I’m probably better as a retail investor than I was as a professional. I tend to be more risk adverse, and this is not optimal for the industry. Let’s put it that way.

Like one of the fun things, where every everybody I work absolutely enjoyed playing poker. And I hate poker. I mean, that was interesting. I think in terms of the whole sort of like the index investing thing. I think the my reputation has been somewhat exaggerated in the FIRE movement. I mean, I wrote a few posts and asked some questions about the systemic effects mass adoption of index investing could have on the markets as such. And that sort of eventually turned into, “this Jacob guy who just hates index investing”. I think my bigger concern was the whole fire-and-forget attitude. Let’s, just hand everything over to an app. Let’s, you know, you want to want something quick and easy, something simple. So just do that. And then you can forget about it.

Mad Fientist: I’d be interested to hear what you think of the FIRE movement? Especially, I think maybe 2017-2018 just seemed like it was going crazy. What were your thoughts on it at that stage? Because this is, you know, seven years after you felt like, you’ve pretty much said everything you wanted to say about it?

Jacob: Yeah, I mean, it’s kind of like doing the podcast today. It’s like, well, man, I just like the 10 years ago, I’d forgotten all about it right now. And I need to revisit my notes, essentially. Yeah, I mean, it definitely hit the mainstream at that at that point. And, you start getting contacted by various journalists, because I mean, I’m sort of still known as one of the progenitors of it. And so of course, they want my opinion on it.

And I think what happened, essentially, you get, like a different kind of different kind of exposure. I mean, if you started if you go like, way back, way back, if you go back to sort of like this, the present iteration, which I think kind of started with me, we were only like, at least I was sort of like the loudest loud mouth bunch, right? I mean, I remember sort of, I mean, back then FIRE was not a thing, that sort of financial independence was not a thing in the personal finance world. I mean, when I was starting up, I was like, you know, these like, blogging awards, and I was I was getting them for, for something like “Best in Senior Living”.

Like “Best Entrepreneurial Blog”, like I hadn’t started into business, but that was sort of like the sort of the framework of sort of like the mid late 2000s that financial independence could fit into.

And so I started out at this very extreme kind of thing, way out of the left field, you know, like, let’s try not buying anything for a year. So that was completely unusual to do that. And when this has now become sort of like a “Buy Nothing Year”.

Back then was David Bach thing where it was like the latte effect, where if you just save $2 a day, you become a millionaire in like 100 years, or whatever, and the idea of retiring was that you would save up a million dollars, it was always a million dollars, so that he was to become a millionaire. Investing, I think, like the 4% rule…that was the thing. But it wasn’t really that wide widespread. I mean, it came out of the Trinity study but back then the Trinity study was only like 10 years old or something. So it was not the foundation of any way to sort of invest for retirement. It was more like I want to retire on this day and I have the $700,000 and I want to spend $40,000 a year, and then they would go back way around and then compute like a return of investment of 6% and so given those 6% what should the allocation investment be like. So that was sort of like pre 4% rule as a as a rule of thumb and a lot of people retired and invested accordingly.

Right. And that kind of goes back to that warning about not adapting or sort of like integrating a very simple understanding of how to invest for the next 60 years, because some of these guys, you know, like, who retired in the 90s. And it was sort of like a mental model that sort of crashed and burned, because investing in some something aggressive at 8%, which was perfectly possible in the 90s, did not work very well between 2000 and 2007.

Mad Fientist: So, would you be willing to share like sort of what your thinking is, as far as personal investment now, and like, you don’t have to obviously share any numbers or any actual strategies, but maybe just give a sort of an idea of what you’re thinking as far as how you invest your own FI portfolio?

Jacob: Having invested for almost 20 years, now, I can definitely say that it changes, I mean, it changes, you change, depending on where I make money, I don’t make money. Depends on how big the network has become. I mean, if you are like starting in the beginning, then index funds, for example, makes like great sense. Because you’re not you don’t have to think very much think very hard about and you can concentrate on your salary instead, I mean, and sort of like a we agree way to identify that demographic is when they plot you know, your net-worth graphic, and it’s just a straight line up, right? Because stuff, you know, your dollar cost averaging is completely and utterly dominating the sort of market impact of whatever your net worth is like, maybe you’re, you probably have sort of like less than 10 to 15 annual spend so that’s essentially how we calculate net worth these days, like how many years of spending have saved. So if you’re below 15, then you know that the net worth curve always tend to be a straight line, because it’s dominated by salary. But then once you sort of get into get into the 25 Plus, and if you get even higher, I mean, my problem is, essentially, I spend so little that whenever people pay me money, I don’t know what to use it for. So this like, just keeps going, going up and up and up. I mean, right now, it’s like 130. And from that perspective, you know, like, volatility, or risk…risk for me is no longer volatility risk, for me is a permanent loss. Right? Maybe that’s another sort of like practitioner takeaway. These guys don’t care about volatility, they care about money that never comes back, right? Because volatility is only really relevant if you’re like, if you’re doing research, then volatility is sort of like, sort of like a very easy way to define risk, because you can calculate, you know, it’s the standard deviation, essentially. And it’s useful if you’re, if you’re a bank, and you’re sitting in the middle between a customer and a big pool of money, because I’m here to sort of like bridge between and you have like slippage losses. But for practical people, that’s the risk of permanent loss. So my personal strategy has tended towards becoming like a lot safer, you know, like belt and suspenders kind of stuff.

My interest in investing, investing is also kind of going down. So I actually might end up just like, putting everything into a Global Fund, or something

I think I worry most about are the cases where someone comes in and says, I don’t care anything about investing or finance or anything, I just want sort of like a one stop solution for my post-FIRE life. I don’t know what what to call that risk…like an ignorant risk or paradigm risk?

Because I mean, paradigms change. I mean, they change every 10 years. I mean, you only have to go back 10 years, look at the real estate bubble, and see how that was sort of like, in many ways in the US, not in Canada, where it didn’t pop. But here, it was many ways driven by by sort of the same dogmatic slogan based understanding that you tend to see in sort of, like, I wouldn’t say it’s like the entire FIRE movement, but there are many, many in the, in the fire movement that have had sort of like the same thing like, well, they’re not making any more land, just by the biggest house, you can, because you’ll never get this chance again. They’re not making any more often. Just paint the walls essentially.

And you can, you can go back and see these kinds of ideas like fail over and over and over again. Because people change their mind. I think it’s like a twofold I mean, you can sort of feel the two ways you can have the paradigm shift under you, and then essentially like miss the terrain. Or worse, you can keep insisting that that one strategy you learned when you’re 25 is still valid when you’re 50, right?

So like, so the dominant paradigms are essentially been index investing since the 2010s is like when that exploded, and part of the reason it exploded was, of course, because interest rates were both dropped and then you had all these quantitative easing things, both in the US and in Europe. And you could actually plot like the stock market index with bands when when you have quantitative easing, the market goes up, when the easing stops, it goes flat. When it started again, it goes up again, you know, that’s not that’s, that’s not really a booming economy. That’s like, an economy, on heroin or something. I mean, that’s just bad. And then you can’t keep doing that forever. What I mean, so far, so good, right?

And if you if you sort of, if you said like this is what’s actually happening in, in sort of, like the practical world, and on Wall Street, I mean, I knew a bunch of like, value investors. That’s not what I was doing, but people doing value investing, and sort of like getting depressed. Because everything was like completely overvalued. There was like nothing to buy that made some sense, right? So they’re just sitting on piles of cash waiting and waiting and waiting. And if you’ve been waiting for 10 years, right?

You can’t keep insisting that you are right and the market is wrong. I mean, you can only do that so long. So that’s the tricky part.

Going back, so you had like real estate in the 2000s. And a little bit again after it recovered, people got into it again, and now it’s called house hacking. It’s always a new new word.

You had .coms in the 90s but obviously, not anymore, right?

A little bit again…the five biggest companies in the s&p 500, that’s 20% of the index, right? They call the giants like Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Google, and I totally forgot one. And they’re like, 40% of the NASDAQ. How’s that for diversification?

Anyway, go back again…So in the 80s, it was commodities and CDs, like bank CDs, because the interest rates were so high. You can’t get anything out of that anymore. So like a safe CD investment from the 80s would completely bomb, right.

70s, gold. My uncle collected stamps. Essentially because the market flatlined, and bonds were not doing anything so people were just buying collectibles, thinking that that would sort of be the thing.

In the 60s, it was like blue chips. I just want to buy the big companies, and you’ll be safe forever. And as a result of that the multiple expansion was immense. So similar to what you see today, in internet stocks, you know, we had like PE ratios above 50. So like, that would take decades for these people to actually like return a decent amount of sort of like economic profit, as opposed to just like greater-fool profit of people like buying higher and so on.

So I mean, the thing is, the biggest mistake one can make is to believe that you, you know everything there is to know about investing. But sort of like you have this kind of like dogmatic mind. I’m not kind of like super insist that everybody become an expert on this. But I do think that I think the least people can do or should do is sort of like pay attention from time to time, like is index investing still a thing? And if it is, cool…just keep doing that. But if everybody around you have sort of like moved on to something else, whatever that is, maybe it’s time to start questioning whether you are still the genius you think you are right.

Mad Fientist: I think that’s great advice. And it seems like right now is potentially a paradigm shifting event COVID and then all the money being pumped into the economy. What are your thoughts on that? Have you have you spent any time thinking about what this means for the next decade? And what’s going to be the big thing for that? Because it does seem like this is a turning point, potentially, in how people think of investments and what the government’s ability to get involved is.

Jacob: Oh, well, investment wise, I haven’t really done much. I was already like a belt and suspenders.

I mean, it was kind of shocking to see things dip that fast, right? That was crazy fast compared to say 2008. 2008 was sort of more like a slow grind. I lost 1% today, tomorrow I lost another percent. And after 30 days, you know, you’re just sort of getting punished every every day until you’re sick of it. And then when when the maximum number of people were sufficiently sick, it flipped, because there were no more that were willing to sell and it went up again.

Here, it was more like slam slam, and then suddenly way up again…it was crazy volatile.

So there was like a lot of people in the futures market that just had like a field day with that. So for them it was good but for buy-and-holders, it must have been very interesting.

But of course, the government immediately practically guaranteed all their corporate bonds, right. So they were dropping. So you have like AA rated bonds, that should normally be almost like treasuries losing, I don’t know, 20-30% like over a week. I mean, that’s insane. And then they gain it just as fast, as the government comes in and backstops the whole thing. What’s more interesting to report on COVID from the ERE perspective, because ERE was originally not intended to be some FIRE thing. It was certainly more intended to be be sort of like a resilient lifestyle, like a low resource intensive lifestyle. So if we were to run into limits to growth in the environment, would it still be possible to live live well. And so for me, it has always been about, highly efficient living, and how to make it resilient and not become financially independent, as much as becoming like economically dependent, like independent of the economy. And so that, essentially is like ERE at the higher level. And if you do that, then FIRE just become a nice side effect. You know, if you have a job, people pay you money, but you don’t have anything to use it for so you just park it in a savings account, which is actually what I did myself for, like the first five years until I found that there was something called investing and the crazy idea, like using money to make more money. I mean, that was just bizarre to me. I mean, I’m an immigrant. I’m from Denmark, where like, stock investing was not a thing, and really wasn’t. Put money in bricks in housing, but owning stocks and bonds, that was just weird. So with COVID, you know, being independent of the economy already, there was like practically no change in the way we live here. And on the forum, we had sort of like a slight tension between what you would call like the traditional FIRE people sort of like high incomes and total belief and like comparative advantage…it’s kind of like the, I’m not gonna spend my time fixing a flat on my bicycle for $15 when I’m making like $50 an hour. So you see that attitude a lot, especially the more people earned, the less they are willing to deal with the little things.

And they suddenly realize, it doesn’t really matter I have all this money when everything is on lockdown and I can’t do anything. Whereas for sort of like the resilient system I build up and then some of the other guys that build up instead it was like wow, this is what we’ve been prepared for practically. And so there was actually a lot of shifts in sort of like the one dimensional money only consumer/producer kind of thing, towards the sort of like more systems theoretical way of integrating your production and your consumption in your personal life so you’re no longer just having money coming from this side, so you earn it here and then you buy stuff here to solve the problem. It was more like the total solution.

Mad Fientist: That’s one of my favorite parts of the actual book. And ERE is one of my favorite finance books and it’s not even really a finance book, as you said. It’s more a philosophy book about overall life strategy and systems and yeah, the the financial independence part is a byproduct of that life but it’s the systems approach to lifestyle lifestyle design that I really enjoyed and I still think about it a lot.

Like when Mr. Money Mustache bought that piece of property on Main Street and had this like community thing. I thought, that’s a such an amazing idea because I’m an introverted guy but I do enjoy meeting people in my community and socializing. I was like, that’s a great idea. And now he has this place that just sort of, like promotes that.

And at the time somebody was talking about maybe starting a brewery. And I thought, oh, that would be ideal because you get the forced socialization, you’re building something, you’re building a business, which is always fun and challenging. But on the health side of things, which in your book, you talk about how the second order effects of some decisions and how it could be negative positive. And for something like a brewery, it’d be great for the community, the socialization, the challenge, the creation/creativity, things like that. But it’d be terrible for the health side of things, because I would find myself drinking more beer.

So it’s definitely something that I’ve kept in mind over the years. And it really does help me make decisions. And it’s like, okay, this seems good at first but what’s the knock-on effect? So yeah, I was wondering if you could maybe talk about how you’ve used that thinking in designing your life and how that has made you really resilient for a pandemic?

Jacob: Yeah, I mean, so like, I almost feel like sort of like, describing the whole thing. Like, the book is very much about like, contrasting and comparing what we grew up with taking for granted, which is essentially the idea that you specialize in a job, you get an education, you specialize in a job that gives you earning power, and then you potentially measure how successful you are in terms of how high your earning power is. I mean, in the English language, we even have like expression, how much are you worth? I mean, when, when we ask that question, we want to know, like, you know, it’s the money question, practically.

It’s not like how nice a person are you or what did you do for your community. I mean, it’s really, are you making lots of money. And along the same dimension, happiness equals spending. And I mean, I don’t know if I’m, like, projecting too much, but you can see how, how FIRE kind of developed into lean FIRE and fat FIRE. I’m obviously somewhat even more extreme than lean FIRE, but fat FIRE often sort of accuses us on the other side of like living a life without happiness because we are sacrificing so much, because spending is happiness. So I mean, it’s not surprising, from even like, from you’re like 10 years old, from the time you’re old enough to watch ads, right? I wonder when that when that happens by age three? You do get sort of like continually reinforced that if you buy something, that increases your happiness, you get a shot of dopamine. Or if you had a problem, you pay someone, so all you need to do is earn and then you buy. So you’re in this kind of cycle.

Personal Finance when when I started with it sort of tried to step out a little bit of that. I mean, if you’re sort of into the spending equals happiness, it’s no surprise that like half of Americans end up not having any more than $400 for one emergency. Right? Which is tragic, crazy. I mean, it shouldn’t be that way, right?

So like, initial personal finance then becomes about like prioritizing your spending and not just like blowing your money left and right and then trying to keep everything together with credit cards.

And people started learning how to budget you know, that’s a basic skill. I don’t know if they teach this in schools today. They didn’t when I was young. To a large degree, people are not taught sort of like the fundamentals of the society they live in it’s kind of like fish swimming in water, right? I mean, they’ve not discussed the water ever. So to them the water does not exist. And to a similar degree, the whole idea of earning and buying as a lifestyle is not something people see from the outside. It’s something that they can’t see because they’re inside of it.

So, in the blogging world, it’s almost like getting an education, when you get into this, from sort of being blind to the water and then getting out.

So you learn to budget and prioritize. And then if you’re a little bit more advanced, you start optimizing your budgets. Where is my money spent best or how do I get the best deal out of this. But it’s still sort looked at in isolation. Like, what is the best car here? Does this car make me happy? You know, are we getting the maximum return of my money in terms of like, my choice of driving, how do I make the best food.

So it’s all sort of like seen as individual things to optimize. You want to spend money well so you have all these like Consumer Reports review. And the underpinning of all this is of course, specialization and comparative advantage, people are distinctly sort of like pushed back towards, you just got to earn more money, because you’re wasting your time if you try to learn other things.

You can suspect that half of the economy is just in the, in the business of like creating problems for the other half of the economy to solve.

I mean, this kind of like with the brewery. So you drink beer to become happy, but then you also become unhealthy. And then you have to take some other drug that makes you healthy again, but that drug has side effects. And now you have to take a drug to remove those side effects and perhaps pay someone to administrate that whole business.

So this is kind of where the ERE book, where that philosophy comes in, because first of all, it kind of describes this screwed up system we’re living in. So it kind of like takes the fish out of the water. Look fish, you’re swimming in this pool of water.

So I introduced the concept of the Renaissance man or Renaissance person, which was sort of like an early idea of the Enlightenment. Today, it’s more like a general polymath, I think would be the right word.

But essentially, the idea that humans have potential to become many different things, and you should strive to develop in that way. You can kind of contrast it with today where any kind of education development practically stops after college. But you should also development in many other directions, like you should be healthy, should to be able to sing, dance, play an instrument, create art, all kinds of things.

So essentially, in the Renaissance idea was the view that a person should be skilled in many things, which is like completely different than the industrial idea that you should be like skilled, very skilled but in only one thing.